Note: views expressed in this article are my own and do not represent the views of any organisation I’m connected to. I’ve put a lot of effort into ensuring the information is accurate and reliably-sourced, but these are complex topics and I’m learning as I go; constructive feedback and corrections are welcome.

A bit of background

I love nature; being outside in the forest or the mountains or the sea makes me happy. It turns out this isn’t just me: studies have shown that being in “direct contact with natural environments” is good for our mood, mental health, and cognition [1]. But our natural world is being lost and degraded, with 75% of Earth’s land surface significantly altered by human use [2]. We’ve lost 32% of the world’s forests since pre-industrial times [2]**, 35% of wetlands since 1970 [3], and 14% of coral reefs since 2009 [4]. Globally, wildlife populations have declined by 69% since 1970 [5] and species extinction rates are accelerating [2]. Australia is not doing well on this metric—we rank 4th in the world for the highest number of animal extinctions and 8th for plant extinctions [6]. There are currently 2,061 Australian species listed as threatened under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act, with 103 of these already extinct [7].

Over the last decade, I’ve felt increasingly depressed by these declines and frustrated by my lack of power to change things. I’m not a politician, a climate scientist, or an ecologist, so what did I have to offer the environmental movement? My personal efforts to live more sustainably felt insignificant in the face of industrial destruction.

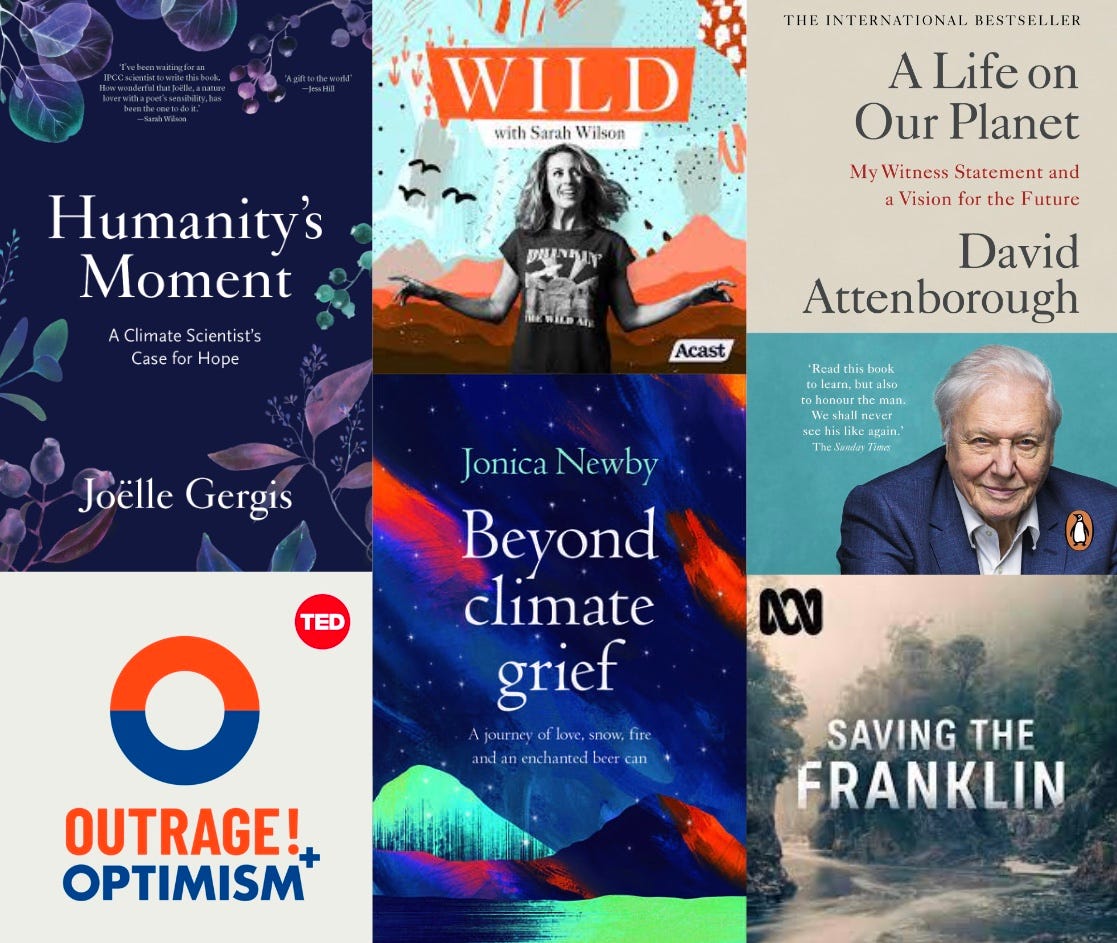

I started devouring books, podcasts, documentaries, and scientific papers, looking for something to give me hope or insight into how I could make a difference. It took a few years, but eventually some recurring themes started to sink in. I began to look at the world a little differently, a little more optimistically. I even started to feel a bit powerful.

Three of these themes stand out in my mind:

The idea of measuring our personal carbon footprint was originally promoted by the fossil fuel industry as a deliberate (and successful) tactic to shift public focus from systemic change to individual responsibility [8, 9].

Most politicians care about what their constituents think and we can express this with more than our vote. Emails and letters will be read by a staff member and counted, and we can even arrange meetings or phone calls to talk directly about issues we care about.

It only takes 25% of the population to drive large-scale social change—to change what’s considered socially acceptable and what isn’t [10].

Joëlle Gergis describes this beautifully in her book Humanity’s Moment: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope [11]. Here’s one of my favourite passages from it:

“Shifting the blame from the criminal actions of destructive industries to individual behaviour has had the insidious effect of many people feeling powerless to do anything meaningful to address climate change. But when we fall for this trap, we allow ‘business as usual’ to continue unopposed by the very people who ultimately create or remove the social licence needed to keep trashing our planet. When we wake up to the fact that we collectively have the power to transform our social and political systems, we can correct our course and steer humanity out of the treacherous seas of greed and apathy, back to the safe shores of sanity and wisdom. We just need the moral compass of our shared humanity to guide us home.”

The best ideas come when you’re taking a break…

One evening in early 2023, I needed a break from all this how-to-save-the-planet stuff and looked for an escape on YouTube. Some of my favourite things on the internet are Beau Miles’ films, so I found myself searching for anything he’d worked on that I hadn’t already watched. I came across a Patagonia film, End to an End: Running to Save the Great Forest, featuring ultramarathon runner Majell Backhausen. I expected the film to be based in the US but the forest looked strangely familiar. Majell was running through Mountain Ash forests in the Central Highlands of Victoria, right near where I grew up. Over the course of a 273 km run, the film highlights the extensive clearfell logging of these forests, its impact on threatened species and Melbourne’s drinking water supplies, and the proposal for a Great Forest National Park.

These Mountain Ash forests are the ecosystem with the second highest documented carbon density in the world, after California’s Coastal Redwood forests [1]. The film explains that when this forest is logged, only 2% of the biomass is turned into fine timber products. The rest becomes pulp, short term timber (e.g., pallets), waste, or is left on the forest floor to decompose or be burnt. The logging is conducted by VicForests, a state-owned business that manages state forests on behalf of the Victorian Government. VicForests has been operating at a loss in recent years, costing Victorian taxpayers $10.1 million in 2020, $4.7 million in 2021, and $54 million in 2022 [12, 13].

I was angry. I grew up in this region—hiking, running, and driving through these forests—and cared deeply for the environment. How did I not know this was happening? And who else doesn’t know, but would care if they did? I followed the link in the film credits to find out how I could help, but it just took me to a page to donate to the Great Forest National Park campaign. I considered donating $100, but it felt inadequate.

And then something clicked. I can run. I also know a lot of runners who love the outdoors. Maybe we can mobilise on these issues?

Small beginnings

I decided I wanted to do my own run through a forest in need of protection. The initial goal was to raise awareness of conservation issues within my local Canberra running community and fundraise for a relevant non-profit organisation. I started talking about the idea with my running friends and they got excited. Things snowballed unexpectedly. Plans for a solo run turned into something way more fun: a community coming together to learn about our native forests and advocate for their protection.

To be continued in Part 2.

Thanks for reading! If you’d like to hear more, please hit the subscribe button below to receive future posts via email. You can also follow along on Instagram and/or Facebook, which are currently more up to date than the blog. If you have a question or you’re interested in getting involved, feel free to reach out at runfortheforests@gmail.com.

**I found it surprisingly difficult to find consistent data on the state of the world’s forests when researching for this article. Different countries and jurisdictions measure it in different ways, and most don’t account for forest degradation (distinct from deforestation). I’ll probably do a future post exploring this topic in more detail, but as a starting point, this ABC News article does a good job of explaining the situation in Australia.

References

[1] Parmesan, C., M.D. Morecroft, Y. Trisurat, R. Adrian, G.Z. Anshari, A. Arneth, Q. Gao, P. Gonzalez, R. Harris, J. Price, N. Stevens, and G.H. Talukdarr, 2022: Terrestrial and Freshwater Ecosystems and their Services. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 197–377, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.004.

[2] IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) (2019) Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services [Brondizio ES, Settele J, Díaz S & Ngo HT (eds.)]. IPBES Secretariat, Bonn, Germany.

[3] Convention on Wetlands (2021) Global Wetland Outlook: Special Edition 2021. Gland, Switzerland: Secretariat of the Convention on Wetlands.

[4] Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN) and International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) (2021) Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2020 Report. [Souter, D., Planes, S., Wicquart, J., Logan, M., Obura, D., Staub, F. (eds)]. doi:10.59387/WOTJ9184

[5] WWF (2022) Living Planet Report 2022: Building a Nature Positive Society. [Almond, R.E.A., Grooten, M., Juffe Bignoli, D. & Petersen, T. (eds.)]. WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

[6] IUCN (2022) The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2022-2. Table 6a and 6b. Available at: https://www.iucnredlist.org (Accessed: 5 Nov 2023).

[7] Department of the Environment (2023) In: Species Profile and Threats Database, Department of the Environment, Canberra. Available at: https://www.environment.gov.au/sprat (Accessed: 5 Nov 2023).

[8] Schendler, A. (2021) ‘Worrying about your carbon footprint is exactly what big oil wants you to do’, New York Times, 31 August. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/31/opinion/climate-change-carbon-neutral.html (Accessed: 8 November 2023).

[9] Solnit, R. (2021) ‘Big oil coined ‘carbon footprints’ to blame us for their greed. Keep them on the hook’, The Guardian, 23 August. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/aug/23/big-oil-coined-carbon-footprints-to-blame-us-for-their-greed-keep-them-on-the-hook (Accessed: 8 November 2023).

[10] Berger, M. W. & Sloane, J. (2018) ‘Tipping point for large-scale social change? Just 25 percent’, Penn Today, 7 June. Available at: https://penntoday.upenn.edu/news/damon-centola-tipping-point-large-scale-social-change (Accessed: 8 November 2023).

[11] Gergis, J. (2023) Humanity’s Moment: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope. Collingwood: Black Inc.

[12] Perkins, M. (2023) ‘Taxpayers billed $38 million as logging agency fails to supply timber’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 March. Available at: https://www.smh.com.au/environment/conservation/taxpayers-fork-out-38-million-as-logging-agency-fails-to-supply-timber-20230307-p5cq1a.html (Accessed: 8 November 2023).

[13] VicForests (2022) VicForests Annual Report 2021–22, Melbourne: VicForests. Available at: https://www.vicforests.com.au/static/uploads/files/vf-annual-report-2022-final-201222-wfjdjhwlojpk.pdf.

Good stuff Courtney! Looking forward to part 2